Unpacking the TRIPS Waiver and Its Impact on India

What impact will the waiver on intellectual property protections on COVID-19 vaccines have on India and the rest of the developing world?

Hi there, I’m Aman Thakker. Welcome to Indialogue, a newsletter analyzing the biggest policy developments in India. The aim of this newsletter is to provide you with quality analysis every week on what’s going on in India.

Thank you very much for subscribing. My writing, and this newsletter, benefits from your feedback, so please do not hesitate to send any suggestions, critiques, or ideas to aman@amanthakker.com.

Unpacking the TRIPS Waiver and Its Impact on India

Since October 2020, India, along with South Africa, has been pushing for greater flexibility and relaxation in vaccine intellectual property rights at the World Trade Organization in order to level the playing field between developed and developing countries when it comes to access to COVID-19 tests, medications, and vaccines. Last week, those efforts got a boost when the Biden administration signaled its support for India’s proposals. So let’s dive into this issue for this week’s edition Indialogue. What is TRIPS? Why is India seeking a waiver? And what impact will such a waiver have on India’s vaccination campaign?

In 1995, the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS Agreement), which requires all signatory countries of the agreement to pass and enact laws domestically that would guarantee that the minimum standards of intellectual property protection would apply within their countries, came into effect. Such standardization of intellectual property allowed companies and innovators to conduct business globally with the knowledge that their intellectual property would safeguarded no matter which domestic jurisdiction they were in.

However, the TRIPS agreement does include some “flexibilities” in times of public health crises. Article 27(2) of the TRIPS Agreement allows signatory countries to “exclude from patentability inventions, the prevention within their territory of the commercial exploitation of which is necessary to protect ordre public or morality, including to protect human, animal or plant life or health.” Section 30 further empowers states to “provide limited exceptions to the exclusive rights conferred by a patent.”

The ability to enforce these flexibilities was reiterated in the 2001 Declaration on the TRIPS agreement and public health, which stated that the signatories agreed that “the TRIPS Agreement does not and should not prevent members from taking measures to protect public health. Accordingly, while reiterating our commitment to the TRIPS Agreement, we affirm that the Agreement can and should be interpreted and implemented in a manner supportive of WTO members' right to protect public health and, in particular, to promote access to medicines for all.”

As such, India has codified these “TRIPS flexibilities” in its domestic laws. Under Section 92 of The Patents Act, 1970, the Central Government of India is empowered to grant compulsory licenses to be issued “in circumstances of national emergency or in circumstances of extreme urgency or in case of public noncommercial use.”

Given these powers and the ability to grant compulsory licenses, why is India seeking additional waivers under TRIPS? Several experts have argued that a compulsory license should be enough to ensure India and other developing countries have access to vaccine without needing additional waivers under TRIPS:

However, others have pointed out that the issue of compulsory licensing is more nuanced and complicated when it comes to vaccines, and that additional waivers are required. Nivedita Saksena, a Fellow with the FXB Center for Health and Human Rights at Harvard, argues that that there are two shortcomings of the compulsory licensing process.

The first is time. She writes on Twitter, “A compulsory license would involve the government permitting someone other than the patent owner to manufacture and sell the vaccine. But first, it's legally required to negotiate with the owner. And if a CL is granted, pay them reasonable royalties. This is not a quick process, and it's almost guaranteed that the patent owner will challenge it.”

The second issue is that, beyond licensing, the production of vaccines requires any manufacturer to have additional details about the manufacturing process, as well as some transfer of technology from the original developer of the vaccine to other manufacturers. As Nivedita Saksena notes, “Vaccines don't work in the same way as drugs, in that they can't be 'reverse-engineered' to make generics. There will be some transfer of technology needed for another company to make them. This transfer doesn't automatically happen when a CL is issued.”

These concerns about the limitations of existing TRIPS flexibilities, including compulsory licensing, is why India is pursuing additional intellectual property rights waivers at the WTO. India and South Africa’s proposals “would effectively exempt countries from enforcing intellectual property rights for coronavirus vaccines and related diagnostics.”

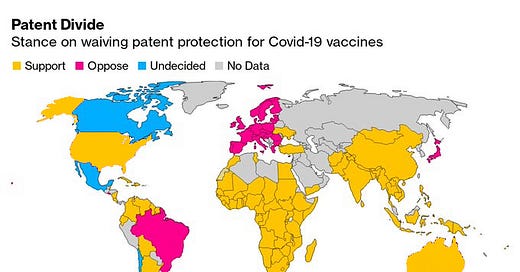

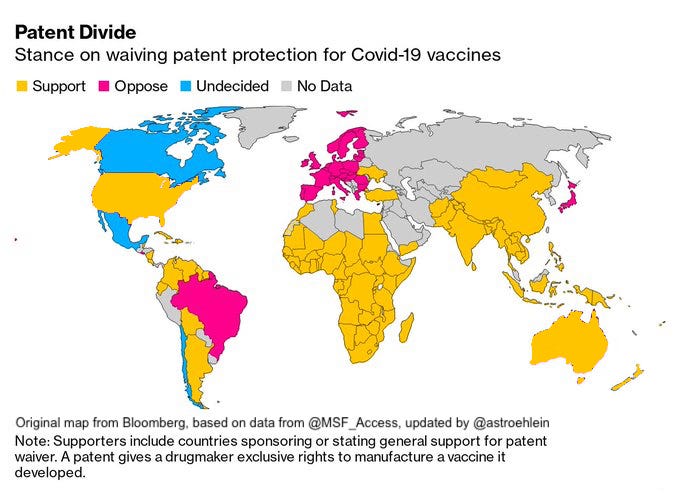

However, their proposal has received mixed support. While a majority of development countries have supported waiving intellectual property protections under TRIPS, several developed countries - the United Kingdom, EU member states, Brazil, Japan, and others - have opposed the proposal. They argue that the focus in intellectual property is a red herring, and that the issue of supply constraints on COVID-19 vaccines is not at all about intellectual property, but about issues regarding scarcity of raw materials and ingredients, as well as capacity to manufacture at scale.

Until recently, the United States was among those also opposing the proposal. However, on May 5, U.S. Trade Representative Amb. Katherine Tai announced that the United States, under the Biden administration, will support the waiver of intellectual property protections for COVID-19 vaccines and “actively participate in text-based negotiations at the World Trade Organization (WTO) needed to make that happen.”

To be clear, the language from Amb. Tai means that the U.S. support for intellectual property waivers falls short of an endorsement of India’s and South Africa’s proposal, but does signal that the United States will negotiate the finer points of the waiver while supporting it in principle.

So what happens next? While the United States’ support for a TRIPS waiver is a big step forward, negotiations to reach an agreement will still take some time. Moreover, even after an agreement is reached, there will likely be very little immediate impact in the supply of vaccines in India or other developing countries. While India does have a robust pharmaceutical industry, other countries will require time - often up to one year - to learning how to set up vaccine production factories and manufacture vaccines.

When it comes to India’s second wave, India will still need to focus on immediate steps to stop the transmission of the virus - ensure physical and social distancing, increase testing, tracing the spread and evolution of variants through genomic sequencing, and vaccinating as many Indians as possible. On vaccinations, India will need to continue to depend on importing COVID-19 vaccines while domestic manufacturers, such as the Serum Institute of India and Bharat Bio-Tech, scale up their own operations to make, store, and distribute COVID-19 vaccines.

However, in the long-term, the TRIPS waiver can be a major step forward in addressing vaccine inequities globally, in which India will play a major role. It is true that it will take time for the WTO to finish negotiating the waiver and that it will take time for India and other countries to receive the requisite information on vaccine production (from the recipe to the necessary transfer to technology to scaling up production of key components and raw materials).

However, the goal of the TRIPS waiver is not to help with India’s ongoing second wave. Rather, it is to ensure that the mantra that developed countries have said over and over to their citizens - that the way out of the pandemic is through vaccines - is true for the world. India is in a unique position in this regard, possessing the manufacturing capacity to manufacture more than 60% of vaccines supplied to the developing world in non-pandemic times. Public health experts have gone so far as to say that “without India, there won’t be enough vaccines to save the world.”

The TRIPS waiver is, therefore, not a short-term fix. However, it is important to ensure that we vaccine the world before the virus keeps mutating, risking the spread of a variant that is more transmissible, more deadly, or resistant to vaccines. And it is to ensure that India can produce the vaccines necessary to ensure we can end the pandemic globally.

If you would like to support Indialogue, please consider sharing the newsletter on social media using the button below!

Five to Read - COVID-19 Edition

Here are a five commentaries and other pieces of writing specifically about COVID-19 and India’s second wave that I found particularly enlightening :

The Lancet, one of the world’s most well-known medical journals, argues: “The Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation estimates that India will see a staggering 1 million deaths from COVID-19 by Aug 1. If that outcome were to happen, Modi’s Government would be responsible for presiding over a self-inflicted national catastrophe. India squandered its early successes in controlling COVID-19. Until April, the government’s COVID-19 taskforce had not met in months. The consequences of that decision are clear before us, and India must now restructure its response while the crisis rages. The success of that effort will depend on the government owning up to its mistakes, providing responsible leadership and transparency, and implementing a public health response that has science at its heart.”

Dr. Ashish K. Jha, dean of the Brown University School of Public Health, writes: “May is going to be horrible in India. June is going to be hard. If we take the steps outlined here, we are going to see real progress in June, and, by July, things may be meaningfully better. But if we do these things in a half-hearted manner now, the nightmare that India is living through now will last longer. India needs a 21st-century health care system. Currently, it has a 19th-century one with small pockets of excellence. As we get out of this crisis, I hope India will prioritise its public health and health care system. Fighting an enemy such as Covid with poor policymaking and an outdated health system is costing too many lives.”

Yamini Aiyar, president and chief executive of the Centre for Policy Research, argues: “India’s Covid-19 response has failed because it ignored a fundamental first principle of good governance — the principle of subsidiarity, which means that the central authority performs only those functions that cannot be performed at the local level and no other. At the start of the pandemic, decision-making was overly centralised. Now, when it comes to tasks where the Centre needs to play a role — procurement of vaccines, supply chain management and allocation of oxygen, human resource and treatment protocols, ensuring resources move to areas experiencing surges — states have been told health is a state subject. Rather than a coordinated response, states are at war with the Centre and each other.”

Samanth Subramanian, a senior reporter at Quartz India, argues: “Why is India, the vaccine factory to the world, unable to find enough vaccines for its own people? There is no single answer, but tracking events over the past year reveals a timeline of dysfunction: a period in which government negligence, corporate profiteering, opaque contracting, and the inequities of the global pharma market combined to bring India to this moment of vaccine crisis.”

Mukta Naik, Fellow at the Centre for Policy Research, argues: “As the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic takes India in a deathly grip, images of returning migrants crowding transport terminals in large cities like Delhi and Mumbai have returned to our television screens. But whereas last year’s long walk home by migrants was triggered by the economic shock of losing livelihoods and compounded by the stringent mobility restrictions of the nationwide lockdown, this year’s return to the villages seems a relatively well thought strategy of exit from cities that are failing to serve even those with wealth and connections. While they continue to mistrust the state, a year of dealing with uncertainties may have improved migrants’ ability to anticipate shock and respond with deliberation and agency.”

News Roundup

Prime Minister Modi participated in a summit with the leaders of all the 27 EU Member States as well as the President of the European Council and the European Commission. This was the first such meeting between the EU and India in the EU+27 format. The summit was focused on three themes - foreign policy and security, COVID-19, climate and environment, and trade, connectivity and technology. A full read-out of the takeaways from the summit is available here.

The Department of Telecommunications, Government of India, formally approved four Telecom Service Providers - Bharti Airtel Ltd., Reliance JioInfocomm Ltd., Vodafone Idea Ltd. and MTNL - to conduct trials for use and applications of 5G technology. They also approved partnerships between these service providers and manufacturers and providers of original 5G equipment and technology, specifically Ericsson, Nokia, Samsung and C-DOT. Chinese companies, such as Huawei, were not mentioned in this release, and therefore not invited to participate in India’s 5G trials.

The Election Commission of India announced that it would defer elections in three vacancies in Parliamentary Constituencies and eight vacancies in Assembly Constituencies across India, which were originally scheduled to be held soon, due to the outbreak of the second wave of COVID-19 infections in the country.

Prime Minister Modi held a virtual summit with his counterpart from the United Kingdom, Prime Minister Boris Johnson, on May 4, 2021. The two leaders discussed the COVID-19 pandemic, established a new “‘Enhanced Trade Partnership,” and launched a new “comprehensive partnership on migration and mobility that will facilitate greater opportunities for the mobility of students and professionals between the two countries.” A complete readout from the summit is available here.

The Union Cabinet Cabinet Committee on Economic Affairs approved the strategic disinvestment of the Indian government’s stake in IDBI Bank Ltd, as wella as agreed to transfer of management control of the bank. Currently, the Government of India and the Life Insurance Corporation of India together own more than 94% of equity of IDBI Bank (GoI 45.48%, LIC 49.24%).

The Reserve Bank of India announced additional financing options for the government, hospitals and dispensaries, pharmacies, vaccine/medicine manufacturers/importers, medical oxygen manufacturers/suppliers, private operators engaged in the critical healthcare supply chain. Under a Term Limited Facility of Rs. 50,000 crore ($6.82 billion), banks can give fresh lending support to emergency health services as they tackle the second wave of COVID-19 infections.

India’s Ministry of Electronics & Information Technology announced that a total of 19 companies - 5 multinational and 14 domestic - had submitted applications under India’s Production Linked Incentive Scheme (PLI) for IT Hardware. The Indian government has set a target for a total production of Rs. 160,000 crore ($21.8 billion) over four years through this PLI scheme.

The Reserve Bank of India announced the establishment of a new committee “to undertake a comprehensive review of the working of Asset Reconstruction Companies in India’s financial sector ecosystem and recommend suitable measures for enabling such entities to meet the growing requirements of the financial sector.”

Prime Minister Modi announced the creation of a new 2+2 dialogue between India’s foreign and defense ministers and their counterparts in Russia. India has so far held similar 2+2s only with the United States and Japan, while it has announced, but not yet held its first, 2+2 with Australia.

Five to Read - Non-COVID Edition

From cogent analysis to potentially big news that you should keep an eye on, here are a few commentaries and other pieces of writing not about COVID-19 and India’s second wave:

Ambassador Kenneth Juster, who served as the 25th U.S. ambassador to the Republic of India from November 2017 to January 2021, argues: “As the U.S. government balances its various interests regarding the S-400 issue, it should recognize that the continued threat of CAATSA sanctions against India is counterproductive in terms of the bilateral partnership as well as the broader U.S. strategy in the Indo-Pacific. The United States should therefore indicate now its intention to grant a waiver in this case, while starting a constructive dialogue with India on the impact of future purchases of Russian military equipment.”

Dr. Garima Mohan, a fellow in the Asia program at the German Marshall Fund, writes: “What is driving Europe’s interest in India? The China factor is one explanation. In fact, European perceptions of India have been changing in tandem with increasing tensions with China. In 2018, the EU released a new strategy for cooperation with India, calling it a geopolitical pillar in a multipolar Asia, crucial for maintaining the balance of power in the region. Reinvigorating the India partnership is also a key pillar of the EU’s Indo-Pacific strategy, as well as those of countries like France, Germany, and the Netherlands (as well as the United Kingdom)… But this is not the only explanation. India has been increasing its political and diplomatic investment in Europe since the mid-2000s, reviving dormant partnerships. This has not always been a linear or perfect process, but the foreign policy establishment is beginning to realize that Europe could be an important partner in building India’s domestic capacities and resilience. ”

Dr. Anit Mukherjee, associate professor at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), Nanyang Technological University (NTU) in Singapore, argues: “The Indian military is currently undergoing a fundamental transformation. These changes are made possible primarily due to the creation, in December 2019, of the post of a chief of defense staff. Armed with a mandate to create joint theater commands, the current chief of defense staff is at the forefront of an attempted structural and intellectual transformation. Successive military crises with both Pakistan and China have added a sense of urgency, and realism, to this effort. Full credit must be given to the prime minister who, early in his second term, is implementing long-promised defense reforms. However, much more needs to be done and greater civilian intervention, and transparency, is necessary.”

Remya Lakshmanan, Hoonar Janu, and Aarushi Aggarwal, members of Strategic Investment Research Unit at Invest India, India’s national investment promotion and facilitation agency, have published a report on opportunities to grow bilateral foreign direct investments in the U.S.-India relationship: “The US is the third-largest contributor of foreign direct investments (FDI) to India as of December 2020. Likewise, the US is the second-largest recipient of outgoing FDI from India. The broad-based and multi-sectoral relationship between US and India is defined by cooperation in areas like defence, commercial relations, energy, environment, technology, and health. As a testimony to these priorities, India and the US have collaborated extensively during the ongoing public health crisis. They have also spearheaded efforts in vaccine development to fight Covid-19. Given the size and sophistication of the respective economies, there is still room for further growth in investments.”

Nikhil Sud, a lawyer and specialist in legal and policy issues related to technology, argues: “While India’s new intermediary guidelines have taken the spotlight in policy discussions, it is critical not to lose sight of another policy that could fundamentally transform India’s technology space: India’s proposal to regulate non-personal data (NPD). The proposal could help if it focusses exclusively on the most critical public needs as they arise, such as Covid-19 induced health needs. But as things stand, the proposal (1) can eviscerate competition; (2) looks harmless to competition, and is therefore even more dangerous (much like how carbon monoxide’s colourless and odourless nature renders it even more formidable); and (3) is part of a deeply concerning emerging trend in India of over-intervention in competition, likely driven at least partially by international developments.”

Thanks for reading this latest edition of Indialogue. Please let me know if you have any thoughts or feedback by emailing me at aman@amanthakker.com.